How Can Manufacturing Achieve Sustainability? A Policy & Resource Analysis

By: Aimee Sukol, JD/MA/MS Ed.

By: Aimee Sukol, JD/MA/MS Ed.

Communication & Policy Specialist

Introduction

As manufacturers, Meta Fab strives to understand how trends, policies, and assumptions impact our industry. As part of their team and a policy specialist, I explore manufacturing’s positioning on sustainability in US economic and public policy to best address industry challenges and better serve the supply chain. In 2020 I evaluated workforce development challenges, history, and programs (see brief summary below) and throughout 2021, I will evaluate trade and environmental policies’ relationship to manufacturing. My examination will challenge the assertion that environmental regulation in itself is harmful or overly burdensome to manufacturing and instead I argue that manufacturing’s unique features present challenges in part because 1) trade policy and global production lack uniform environmental standards and 2) national policy fails to adequately support and incentivize local, green production.

2020 Trade & Labor Policy:

In 2020, I covered the impact government policy has had on manufacturing’s workforce development. Specifically, I noted that trade policy encouraged overseas production that reduced local demand for manufacturing labor and I discussed cultural shifts that emerged over the 20-30 year period of low labor demand. As costs to produce overseas have increased local demand for labor, labor supply has dwindled. My analysis concluded that manufacturing should look at policy nuances for long term impacts to better explain the problem. For example, today we might be inclined to say there is a problem with educators for failing to sufficiently expose youth to the trades when in fact, the issue began decades ago with policy that prioritized the financial service sector over labor intensive industries. Could the trade industry have prevented this outcome 30 years ago? Why did the Made in America campaign fail? We learn by highlighting sustainability policy today for impacts tomorrow.

2021: Environmental Policy

High level policy goals are best positioned to help companies become better stewards of the environment. States and local governments have fewer resources so they tend to prefer regulations and fees to meet green objectives. A national commitment to sustainability affords more incentive funding and professional guidance to explore and implement long term operational improvements and investments. So as we explore different sustainability programs from local to national levels through 2021, I will ask: Do these programs meet the following measurements: 1) accessibility of guidance/support; 2) navigability; and 3) cost effectiveness.

The following is an introduction to a larger examination of sustainability in manufacturing and environmental policy.

Sustainability in Manufacturing as an Industry

Manufacturing is a labor, equipment, and regulation intensive industry. Manufacturers pay fees, licenses, special taxes, and permits that can run into the hundreds of thousands for a small operation. For example, a manufacturing facility that adds a window to the side of a building can trigger $100,000 in costs to repave the sidewalk and add new landscaping. All too often, smaller companies are left to navigate rules and regulations without the costly assistance of a consultant adding to the tirelessness required in this industry.

For most small and mid-size manufacturers, the VP or owner is not making 100x the average employee. The industry’s regulatory responsibilities and operational costs are significant enough that additional considerations and expenses often lead to layoffs or below modest pay for workers. I contend that negative attitudes or resistance to environmental considerations within manufacturing (especially among small and mid-size companies) stem not from disregard for the planet, but from the attitude outside the industry that takes for granted manufacturing’s contribution to our world and the lack of help offered to adopt sustainability. For manufacturers to invest in sustainable practices and remain afloat, accessible, navigable and cost effective programs must exist.

Sustainability in Manufacturing as an Company

Manufacturing companies have at their most basic three core departments: management/executive, office, and shop floor. The simplicity of a small operation increases the odds that protocol is followed; however, with small companies you will also find management wearing multiple, time consuming hats from purchasing, engineering, maintenance, rule/regulation adherence, customer service, sales to shop floor work. This type of company could very well also run a green operation if developed with a green mission, but absent a green business model, this company will struggle finding time and resources to navigate additional work that does not produce a bottom line benefit.

Growth adds complexities and requires additional people, so while individuals are better able to focus on one function, they must still effectively communicate with each other to ensure core expectations are consistently met. If a company with a green business model must take additional steps to ensure different elements of the company follow a sustainability protocol, a company that later chooses to adopt sustainable production will face exceptional challenges.

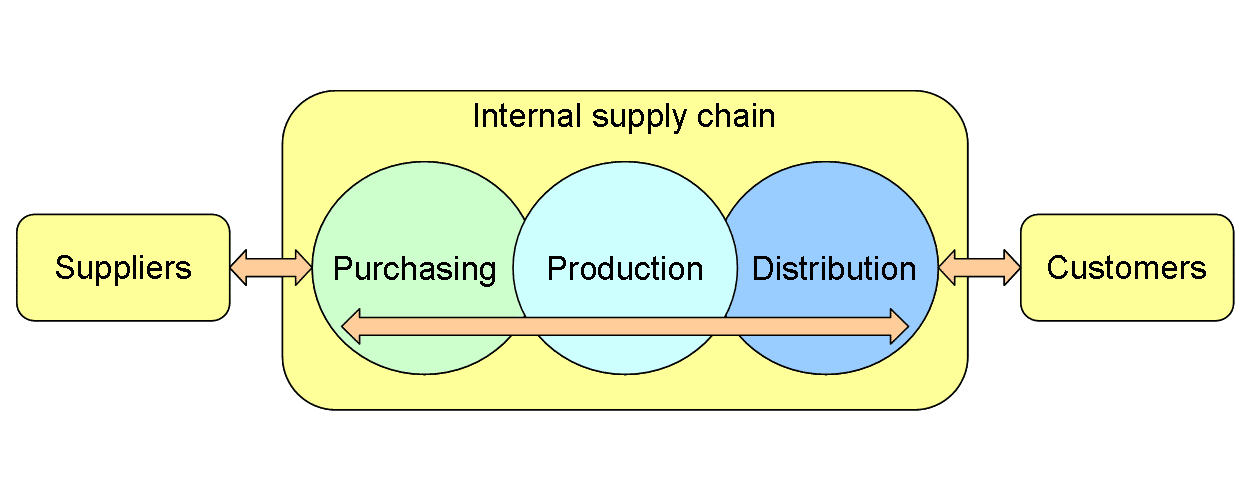

Harvard Business Review studied sustainability programs through the global supply chain from first to last level tier companies. They found that having a sustainability mission within first-tier manufacturers, i.e. Apple mattered because they were in the primary position to uphold green production by conditioning contracts on sustainable practices. However, HBR found that green missions fall apart when there’s lack of organization, training, and monitoring throughout the supply chain. Researchers highlighted instances where purchasers were told to order from a preferred (non green) supplier in violation of the company’s sustainability rules. Internal inconsistencies and lack of training not only created frustration, it failed sustainability objectives.Researchers also found intermediary companies between first and last tier production did not even know to seek a green supplier if the first tier manufacturer did not lay out clear protocol and training. In many cases, a first tier manufacturer did not know the standards or practices of tiers at the end of their production line so an end product touted as part of a sustainable mission may not be green at all.

HBR’s article highlights the complex nature of manufacturing, which is a global effort developed under varying conditions and standards. First tier businesses are where the impetus is often identified, but the fundamental effort is undermined without consistency, training, and coordination. Because manufacturing is incredibly labor and equipment intensive, one can imagine how expensive it is to ensure rigorous attention to a program without a bottom line benefit.

US Manufacturing and the Environment

Trade agreements that resulted in offshoring production also created offshoring of pollution to regions that lacked environmental standards, monitoring, regulation or data; however, environmental and geological experts have spent considerable time documenting the impacts of regional pollution on the global environment. In other words, jurisdictional shopping may lower operational costs and a local community’s pollution levels, but it will not mitigate macro level environmental damage.

Offshoring has been attributed to environmental damage for a number of reasons. First, as noted by HBR the areas of the supply chain outside of the US lack monitoring, regulations and data thereby undermining the purpose of a first tier manufacturer’s global impact mission. Second, transport and packaging to foreign facilities requires a tremendous amount of fuel and resources that could be conserved by using a local supply chain. As Tony Varela of Meta Fab highlighted in his blog, local supply chains and economies not only support a healthier workforce, they reduce resources expended through transport.

In his paper on the relationship between offshoring and domestic pollution, Yue M. Zhou notes that when the EPA publishes its list of the “dirtiest (US) counties,” increased media and institutional pressure encourages plants to outsource pollution intensive operations to lower wage countries. The shift from low local oversight to intense scrutiny often leads to regulation avoidance, not quick adoption of green production. However, the ultimate objective of sustainable manufacturing is not to relocate pollution, but to reduce and eliminate it. Thus, Zhou’s findings support a national policy that coordinates international environmental standards and for the purpose of this article, his findings support national policy that funds tools and guidance for green production that will have a greater net positive than penalties for non-compliance.

Georgetown economist Arik Levinson

argues that US manufacturing has become greener though he factored out the impacts of offshoring. While he cites new technologies and cleaner operations to explain our local reduction in pollution, he only speculates as to why US companies are making these changes. Levinson’s argument conflicts with Zhou in stating that environmental regulations managed to encourage cleaner production rather than drive companies away. It is important to note that Levinson refers to high regulatory environments. While I speculate to some extent here, my own policy background has shown that stricter scrutiny reflects a heightened sense of importance. Thus, plants in communities with high environmental quality standards & oversight may benefit from local resources to support green investments whereas plants in what Zhou/EPA refers to as “dirty counties” that lack local oversight will also lack available resources to improve operations, thus their preference for offshoring to avoid impending federal scrutiny. The latter scenario offers a no win situation as local communities experience pollution until plants are exposed, then pollution is merely relocated.

Two interesting points stand out from Zhou and Levinson’s arguments. One, that the benefits of local production with higher environmental regulations can outweigh cost savings from offshoring to countries with lower standards. The local community’s emphasis on environmental quality and available resources can explain why a plant chooses domestic green production over outsourcing pollution. Two, Levinson did not say offshoring had no impact on the environment. Quite the contrary, he stated that increased production overseas increased pollution, just not in the United States, which is consistent with Zhou’s theory.

Conclusion: Policy Analysis

Manufacturing’s operational costs are significant and numerous. On top of these costs, manufacturers also operate within a labyrinthine global supply chain where middle tier/contract manufacturers are often squeezed between their customers and their suppliers. And it is quite evident that the reality for small and mid-size manufacturers are ignored in the development of trade policies that promote competition with developing countries and public policies that emphasize penalties over guidance and resources. As a result of being ignored, policy discourse within much of the manufacturing industry has been reduced to a fight about the existence of regulation rather than scrutiny of policies that fundamentally burden the majority of US manufacturers versus those policies that really only require adequate funding and support.

I will review specific environmental programs (both funded opportunities and required programs) for accessibility of guidance/support, navigability, and cost effectiveness this year in the context of policy analysis. As I challenged skills gap assumptions that overlooked trade policy’s impact on today’s lack of (or disinterested) labor supply, I challenge industry assumptions that environmental regulation is what harms manufacturing rather than trade policies that encourage competition with no-standard countries and inadequate federal funding to innovate and comply.